RoguesCulture Podcast 7 – History, Fiction & the Truth Beneath the Sugar

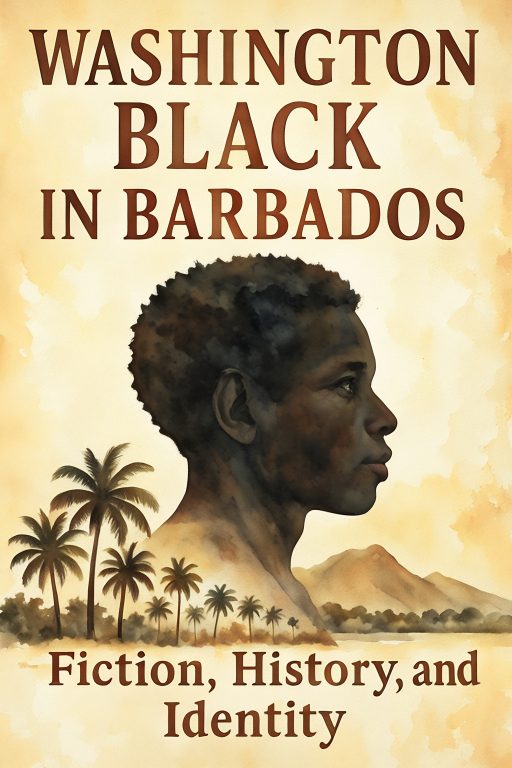

A boy in a balloon rises over Barbados. Below: the brutal cane fields. Ahead: the icy shores of Halifax. It’s the dramatic opening of Washington Black, the celebrated novel and TV adaptation that fictionalises the horrors—and hope—of Caribbean slavery. But behind the fiction lies a more profound truth. One rooted in Barbados, Britain’s first slave society. A place where the Rogues in Paradise lived, resisted, and forged a culture from the spoils of empire.

This RoguesCulture podcast episode explores the real stories behind the fantastical flight of Wash, from the plantations of Barbados to the North Atlantic.

Here is the full transcript of Podcast 7

Imagine this scene. It’s almost, well, it’s almost impossible to picture. An 11-year-old boy, George Washington Black, they call him wash-escaping the absolute hell of a sugar plantation in Barbados. Right. But he’s not running through the fields. He’s floating, floating away in this kind of revolutionary hot air balloon at his destination.

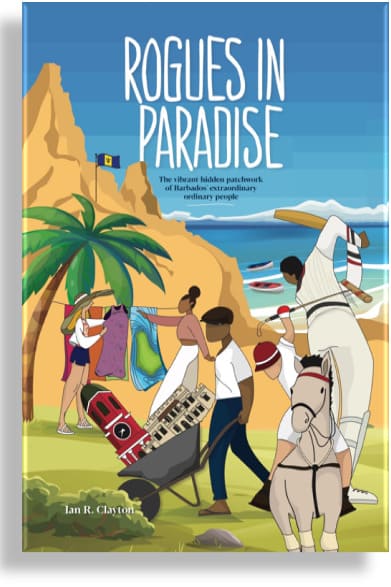

Impossibly, it seems, the frozen, complicated shores of Halifax, Nova Scotia. That’s such a powerful opening image. Isn’t it? That striking visual. It’s right at the heart of Essia Duggan’s incredible novel, Washington Black, which, by the way, is being adapted into a Hulu series soon. Yeah, I heard about that. Looks promising. Definitely. But today, we’re actually going to step back from the fiction, brilliant as it is, and ground ourselves in the real gripping history that makes that fictional journey feel so… So it sits behind the story. Exactly. Our mission here is do a deep dive into the historical threads, the cultural roots that tie Barbados and Halifax, Canada together. It’s a connection that goes back centuries. It’s deeply personal for many and honestly, surprisingly complex. It really is. Our main source for this is a nonfiction book, Rogues in Paradise.

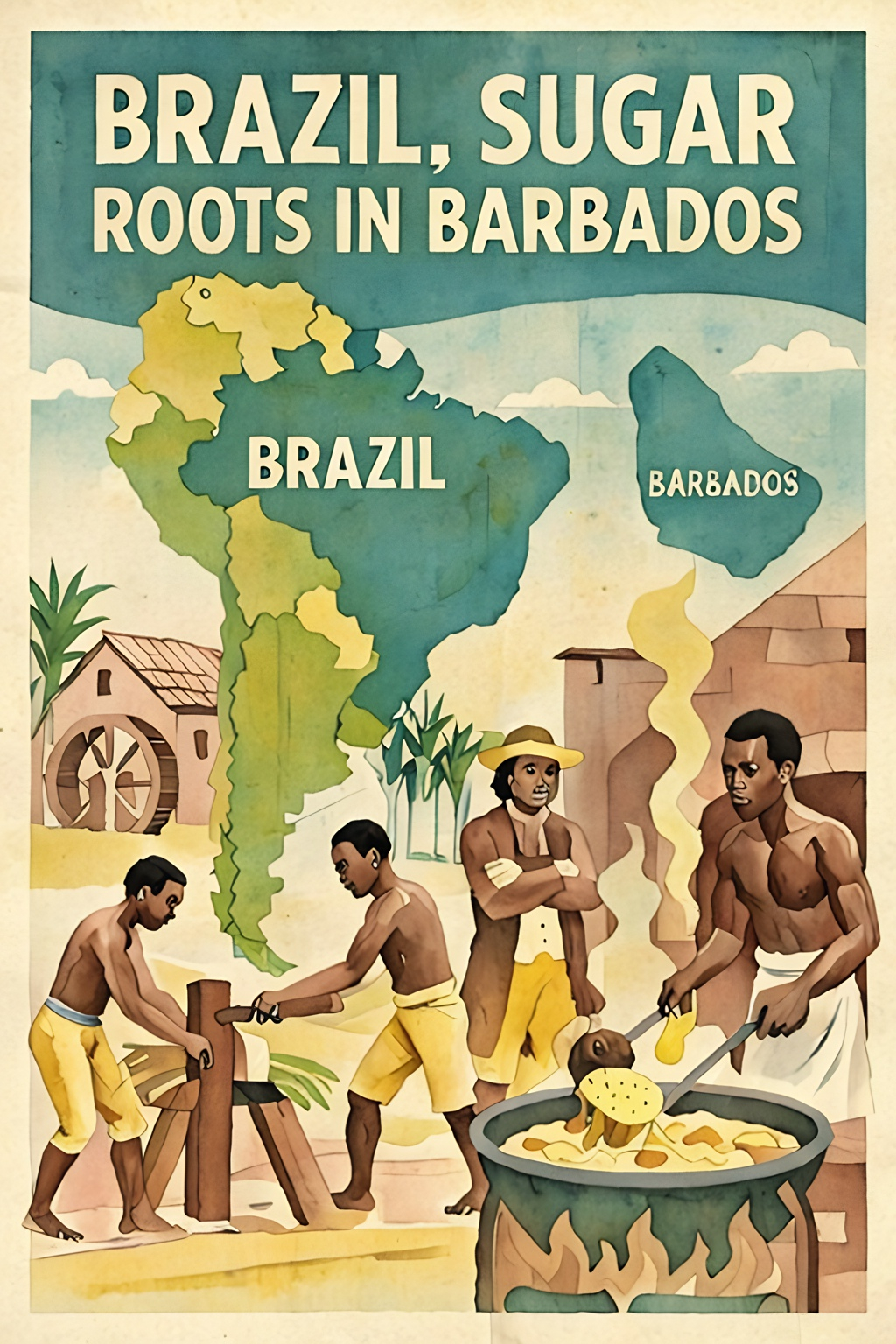

And it works almost like an unofficial companion piece, you know, giving us the real-world backdrop for the world-washed Black fled and the place he was trying to reach. So peeling back the layers of the fiction to see the history underneath. Yeah. We’re asking, how does this fictional journey of one boy mirror the actual struggles, the huge migrations, and maybe the quieter triumphs of the Bajan people across the Atlantic? OK, so let’s dig into this history. Well, to really get why that journey from Barbados to Halifax holds so much weight, you kind of have to start right at the beginning of the British Empire’s Caribbean project. And the really crucial thing to understand about Barbados is that it wasn’t just a slave society. It was effectively the first British slave society, the prototype. The blueprint, you mean. Exactly that. The sources we looked at call it the testing ground.

By the middle of the 1600s, Barbados had developed this ruthless efficiency, sugar production controlling the enslaved population. A horrifying system. Horrifying, yes. And efficient in the worst way. This system was then basically exported across the Caribbean. They even codified it, you know, with laws like the 1661 Slave Code. What did that do? It legally defined enslaved people as chattel. personal property, stripped them of absolutely all rights. This extreme system perfected, if you can use that word, in Barbados, it set the standard for generations of exploitation. Wow. So Barbados is building this machine of extraction and brutality.

The Halifac Connection

Where does Halifax, Nova Scotia fit in? It couldn’t have been totally separate, right? No, not separate at all. Halifax, Nova Scotia played a really critical role and a complex one. Kind of contradictory, actually. How so? Well, initially, it was absolutely part of that same system. Think about it.

North American colonies, including Nova Scotia, they were trading essential goods, timber, fish, supplies, sending them down the coast. To fuel the plantations. Exactly. To fuel the sugar economy in places like Barbados. So they were necessary trading partners within that same brutal framework. Early Halifax benefited directly from the system. Okay, so it starts as a partner in the system, but you mentioned a duality, a contradiction. How does a port involved in that trade become a refuge later on? That seems like a major shift. It is a major shift and it really highlights how complex the British Empire itself was becoming. As you move towards the end of the 18th century and into the 19th, Halifax starts to transform into a crucial destination for freedom seekers, particularly black loyalists after the American Revolution and later those escaping slavery in the American South via the Underground Railroad. Right. The Underground Railroad connection is strong there. Very strong.

So it goes from being essentially a supply hub for the system to a kind of sanctuary against it. And then later still, it becomes a really significant destination for planned migration from the Caribbean, especially after emancipation. And the nonfiction source we’re using, Rogues in Paradise, it really makes a point of grounding this history, doesn’t it? Mentioning the author lives between both places. It does, and that personal connection, living between Halifax and Barbados, it underscores that this isn’t just abstract history, it’s lived reality. It’s as real as it is riveting, I think is the phrase used. And that’s really the engine behind the book, trying to tell the story behind the fiction, focusing on the rogues, rebels, and ordinary people, as it calls them, whose actual lives shape the island and its connections. So it gives us the grounded reality for the kind of imaginative leap that S.E.

Esi Edugyan’s Washington Black shows that the dream of escaping to Canada wasn’t just fiction. Precisely. It was a real historical impulse born from desperate circumstances. OK, so the Washington Black novel is set before emancipation, but Rogues in Paradise really digs into what happens after 1834, after slavery is legally abolished. But, you know, freedom didn’t automatically mean prosperity, right? Far from it. That’s such a key point. Often overlooked. After emancipation, Barbados had this large population, many skilled, often educated people. But the island’s whole economic structure still rigidly colonial. So the legal status changed. But the power dynamic. Not so much. Exactly. The old plantocracy the sugar estate owners they still controlled almost all the land all the means of making a living. So workers were technically free but they were forced into this very low wage system or sharecropping with almost zero chance to get ahead to own land. Right.

So even if you were a skilled carpenter say or a mason. Your opportunities were just capped, stuck, limited by this economic bottleneck on this small island. And that creates the conditions for, well, an exodus. Rogues in Paradise has that really evocative chapter title. Freedom’s hollow echo. Canada, the next horizon. A hollow echo, yeah. Because freedom didn’t immediately fill their pockets or give them land. So thousands of Barbadians, Bajans, started looking elsewhere. And Canada, particularly Nova Scotia and the Maritimes, became this major draw. They weren’t just fleeing poverty then. It was about seeking opportunities for their skills. Absolutely. They migrated with skills. They came to work in the shipyards, which were booming. They served in military regiments. They came seeking better education for themselves and their children. They were actively building new lives. It’s quite sobering, though, isn’t it?

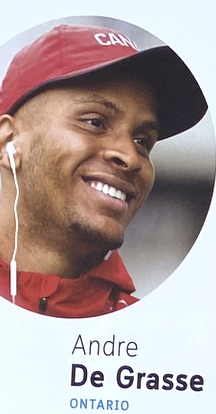

That journey to the promised land, as it might have seemed, often involved facing, well, prejudice. It wasn’t always a warm welcome. No definitely not. The discrimination was usually systemic. It was evident in phenomena such as housing segregation and difficulties finding jobs that matched their skills, despite being highly qualified. So barriers were put up. Yes. Often segregated into specific neighbourhoods, like parts of Halifax. But what’s really striking is the resilience, the Bajan community’s determination, investing in education, building churches, and community groups. That’s what really started to change the Canadian landscape over time. And the influence they had. It’s just incredible when you start looking. We see the impact everywhere in Canadian culture and politics. These aren’t just footnotes in history books. No way. The Bajan Canadian legacy is immense, and it’s truly a story of pioneers breaking new ground. I mean, look at the arts. You’ve got literary giants like Anthony Clark.

Prominent Bajans in Canada

You’ve got these incredible jazz musicians like Oliver Jones and Joe Seeley. Their music often carries those Caribbean rhythms, that diaspora experience. Yeah, absolutely. And it goes way beyond the arts, too, thinking about sports. Andre de Grasse, the Olympic champion, cultural leaders like Cameron Bailey at TIFF, Right. These figures represent generations of families with Bajon roots contributing right at the heart of Canadian life. And the political breakthroughs are so important, too, because they speak directly to overcoming those initial barriers you mentioned. They really do. You look at someone like Leonard Braithwaite. The very first black person elected to a provincial legislature anywhere in Canada. Think about that milestone. Huge. And Senator Ann Coole’s the first black Canadian appointed to the Senate. These weren’t just symbolic appointments. They carried the weight of that whole migration history and really fought to open doors.

That continuity, that thread connecting Barbados and Halifax, it’s so tangible. And it’s fascinating how personal it is, even at the highest levels. There’s that great little story in the source material about Errol Barrow. Yes. Barbados’s first prime minister after independence. The father of independence. Right. And he actually trained where? Right there in Nova Scotia during World War II. He trained in navigation. It just perfectly highlights that this connection it wasn’t just one way traffic. You know Bajon’s looking out to Canada. It was reciprocal expertise leadership flowing both ways. Okay, so we’ve got the historical foundation, Barbados is the testing ground, we’ve got Halifax’s complex role, both partner and refuge, and this powerful legacy of migration shaping modern Canada. A really rich tapestry. So now we have these two powerful narratives running in parallel.

The Limits of Colonialism History

We’ve got the big sweeping fictional adventure of Washington Black, and then the grounded historical chronicle of Rogues in Paradise. Why do we kind of need both to really get the full picture? Well, I think it boils down to something the sources touch on this idea of the silence past, meaning that the official histories of places like Barbados, they were overwhelmingly written by the colonizers. They focused on, you know, trade statistics, ship arrivals, profits, the triumphs of empire. Of the human cost. Exactly. The lived reality of the enslaved people, their daily acts of resistance, small and large, their family lives, their culture, their hopes, their fears that was deliberately minimized or just completely erased from the official record. So the archives, the documents that historians usually rely on, they’re just thin or missing entirely for the most marginalized people. Pretty much. What survived often isn’t in neat government files. It’s scattered.

It’s in fragment for stories. It’s in folklore, in oral traditions passed down whisper by whisper through generations. The written record, the official history, it fails us because it mostly just recorded the perspective of those in power. Okay, so if the archives have these huge gaps, these silences, that leaves a massive emotional void, right? Yeah. An experiential void. How does a novel like Washington Black step into that space? Well, that’s where fiction can do something unique. Edugyan’s novel, as the source material puts it, it ferreted out deeply felt memories from the faintest traces. It reconstructs the emotional truth. What did it feel like to be that enslaved boy, dreaming of flight, seeking self-definition? Fiction can give us that internal world, the psychology, the hopes and fears in a way that, you know, just reciting historical facts never could. It fills in the humanity that the records left out. Precisely.

And that brings us back to Rogues in Paradise, the nonfiction source. It takes a different approach, but it’s also aiming for that recovery just in another way. How does it do that? It’s described as a creative chronicle. It’s grounded in real interviews, documented oral histories, actual encounters. So instead of inventing one fictional journey, it tries to piece together the mosaic of all those absent voices, the collective story. Right. It shows how ordinary, real people resisted, endured, and redefined themselves living under slavery and empire. It takes those genuine fragments of truth and weaves them into a coherent narrative that tries to honour that collective experience. So this dual approach, the emotional depth from fiction, the documented collective experience from the creative chronicle, It really raises a big question about identity and history today, doesn’t it? Yeah.

Why is it important for us now to engage with both these kinds of stories about the Caribbean-Canadian link? Because the legacies we’re talking about, colonialism, slavery, migration, resilience, they aren’t just dusty history. They’re still shaping our present. In what ways? Well, these narratives, both fiction and nonfiction, they open up deeper, frankly necessary conversations about identity, about belonging, about how the past informs who we are now, both individually and as societies. By understanding the structural violence back then and the incredible resilience shown in that migration afterwards, we get a much fuller appreciation for the creativity, the strength, the enduring bonds that really define that whole Caribbean-Canadian story. It’s not just a story of suffering; it’s profoundly one of resilience. Okay, so let’s try and pull the main threads together then. Our key takeaways from this deep dive.

We’ve seen the brutal foundation laid by Barbados, the first British slave society. We’ve examined Halifax’s complex and shifting role from a trade partner in that system to a vital refuge. That duality is crucial. And then the powerful wave of post-emancipation migration that forged this lasting, celebrated connection, creating icons across Canadian culture and politics. Yes, the richness of that connection, spanning centuries and impacting so many lives, is truly something. And I think as we move away from the specific source material now, we’re left with a really interesting question to chew on. Right. It’s the question that sort of ties Washington Black and Rogues in Paradise together and really our whole discussion, which is, how does fiction like Doug Enyan’s novel complement or maybe even challenge a nonfiction chronicle like Rogues in Paradise when it comes to telling the full story of resilience and identity? It’s a great question to ponder.

You could argue maybe that the nonfiction gives us the map, the historical context, the economic drivers, and the why the journey happened. OK, the structure. Yeah. But maybe the fiction, like Washington Black, gives us the compass, the internal, personal, desperate need for freedom that actually propelled someone like Wash across those miles, the human heart of it. That’s a really powerful way to put it. We encourage you, the listener, to think about that. Consider the ways that narrative, whether it’s presented as fact or as fictionalised truth, shapes how we understand history, how we understand identity even today.

Which kind of story resonates more deeply with you and why?

Inspired By The Books:

Rogues in Paradise and Washington Black

From the slave codes of Barbados to Wash’s balloon escape, Episode 7 of RoguesCulture bridges the imagined and the real.

See how stories collide — and reveal a more profound truth. with the Book Rogues in Paradise

More on WashingtonBlack >>>

Footnote on Making of the Movie- From Page to Screen

The screen adaptation of Washington Black is not a direct retelling but a creative interpretation of Esi Edugyan’s novel — expanding its characters and settings to suit visual storytelling. Writer Selwyn Hinds describes it as “the same house, just bigger,” exploring deeper backstories and new storylines while staying true to the emotional heart of the story: hope, agency, and the quest for freedom. In contrast, Rogues in Paradise offers the factual history of that era — a chronicle of real people, places, and events that inspired the fiction.

Making of the Movie Washington Black >>

PODCAST Blogs & Resources

- Washington Black Meets the Real Barbados

- Podcasts Shift to Video: Amazon Says Listen-Only is Broken

- RoguesCulture Rebel Soul Music Podcast – episode #2

- RoguesCulture-The Punk Rebellion

- RoguesCulture Music Rebels

- RogueCulture – Podcasts Rising!

- RogueCulture Asks What Is a Podcast Anymore

- Molten Memories: The Animated Podcast Experience

- Molten Memories- Rogues Culture Podcast 2

- RoguesCulture -The History Of Podcasting

- Podcast Marketing Strategies Added

- Rogues Hybrid Podcast Animated Video

- Overview Rogues Podcast 1 Script