The old man sat beneath a sea-grape tree, its broad leaves flickering like small green shields in the wind. He had the kind of face that held history the way coral rock holds the sea — shaped by pressure, softened by time. When he spoke, it was never rushed. Words came like the tide, deliberate and rhythmic, rising from a depth that felt older than anything written in books.

“You see that house there?” he said, pointing to a weather-worn chattel house perched on a coral stone plinth. “That little wooden thing have more story than half the people who pass it every day.”

He didn’t smile. He didn’t need to. The house itself seemed to nod in agreement — wooden boards darkened by sun, galvanized roof catching the light, steps smooth from barefoot years. It was small, almost fragile in appearance, yet it stood with the quiet certainty of something that refuses to bow.

“That is we inheritance,” he continued. “Not money, not land. Mobility. The ability to move when things get rough. The right to pick up yuh life and shift it where yuh spirit feel more free.”

He tapped the bench with a knuckle, as though he were knocking on the door of memory.

“That, my friend, is the meaning of the chattel house.”

A House that Could Walk

Chattel houses were born in the years after emancipation, when freedom came without land. Plantation owners expected freed people to stay in the same place, working the same fields, in the same dependency. But Barbados had other ideas — and so did the people who built their lives on its narrow ridges and coral plains.

Imagine it: a whole society of people who owned their home, but not the soil beneath it. The chattel house solved a contradiction that the colonial system never intended to fix. Built on loose coral stones instead of foundations, it could be lifted, shifted, swung around, mounted on a cart, rolled by neighbours, and replanted somewhere else — often overnight.

It was architecture as resistance.

Ingenuity disguised as simplicity.

A house that refused to be held hostage.

The elder leaned forward, lowering his voice as if sharing a secret.

“You know what a movable house does to a people? It teach them that belonging is not something to wait for — is something you carry.”

Memory Built in Wood

Note the coral bloaks the house sits on

The chattel house became a kind of portable memory. Every board carried a story: a birth, a quarrel, a promise, a hurricane survived, a prayer whispered through floorboards, a pot singing on a coal stove. Families expanded and contracted, rooms added and removed, house shifting shape the way identity shifts through generations.

“This is why we never lose we humour,” the old man said. “A people who can lift they whole house and move on? You can’t break them. You can only teach them different ways to stand.”

The house was not just shelter.

It was testimony.

A declaration carved in pine and mahogany: We will not be trapped again.

A Symbol of Self-Determination

In a world where landlessness was designed as a form of control, the chattel house subverted the system. It offered autonomy without permission. It made the poorest people in Barbados into homeowners — on their own terms, in structures built with skill, pride, and communal labour.

When a family saved enough money to buy land, the house would travel with them — lifted, balanced, and carried like a treasure. Neighbours arrived with ropes, lever boards, and laughter. Children ran beside the procession. Elders blessed the path with a quiet nod.

“This is what you must understand,” he said. “We didn’t wait for nobody to hand us identity. We build it board by board.”

And in that simple truth lies the depth of the Barbadian spirit.

The Chattel House in the Modern Imagination

tycot chattel house village

Today, the chattel house is often photographed as nostalgia — a picturesque symbol of the West Indies, painted in tropical colours, printed on postcards. But beneath that charm lives a profound cultural legacy.

It influenced the nation’s visual identity, inspiring modern architectural forms with steep gable roofs, verandahs for breeze, and raised foundations. It shaped how communities grew, where roads curved, how villages formed, and how families claimed space on the island.

It also shaped the national character.

A people who inherited portable identity became steady in other ways: disciplined, adaptable, quietly determined, practical, and deeply resourceful. The chattel house taught generations how to weather uncertainty, rebuild with dignity, and stand firm without needing grandeur.

As the elder put it:

“In life, you don’t need a palace. You need a home that move with yuh heart.”

A House as Metaphor for Barbados

Barbados itself is a chattel house of sorts — a small island that refused to stay where the world tried to place it. It picked up its identity and shifted it through centuries of upheaval:

-

Amerindian origins

-

English colonial rule

-

African survival and reinvention

-

The plantation era

-

Emancipation

-

Migration

-

Education

-

Independence

-

Republic

At every turn, the island adapted without losing itself. That is the chattel house spirit.

Mobility without uprooting.

Strength without rigidity.

Identity that travels but does not fade.

Rogues, Identity, and the Spirit of Improvisation

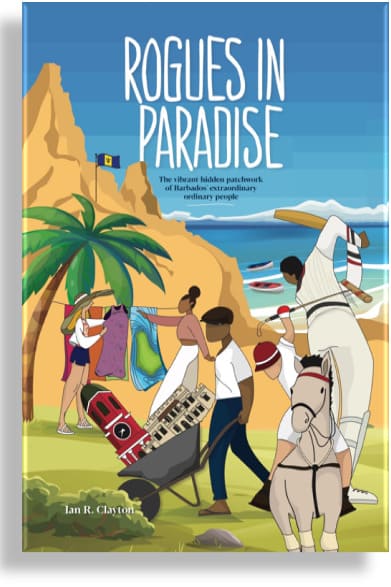

The story of the chattel house belongs in Rogues in Paradise because rogues — in your definition — are people who bend the rules, reimagine the possible, and create new ways to survive and thrive.

The chattel house is a rogue structure.

It defied the plantation system.

It challenged the logic of land control.

It embodied the improvisational genius of ordinary Bajans.

And like the characters in your book — Ace, Woolly, Yardfowl, Muriel — the chattel house was bold, unconventional, and quietly rebellious.

As you often say:

Barbadians did not inherit freedom — they created it.

The chattel house is the architectural proof.

The Elder’s Last Word

The old man rose slowly, dusting sand from his trousers. He turned toward the little wooden house as though looking at an old friend.

“One day,” he said, “people gon’ forget what this house really mean. They gon’ think it was just pretty wood and bright paint. But you — you write the story now. Make sure they remember.”

He paused, letting the sea-grape leaves rustle in the stillness.

“This house is we. All the shifting, all the surviving, all the dreams we pack up and carry from one place to the next. When you understand that, you understand Barbados.”

And with that, he walked away — slow, steady, unhurried — like a man who carried his own house inside him.

VIDEO

This story is part of the deeper cultural journey explored in Rogues in Paradise and the RoguesCulture Identity Series.

If you’d like to explore more stories like this — stories of resilience, humour, rebellion, and belonging — you’re invited to the early pre-screening of the work that started it all.